Italian Powers in the Mediterranean: From the 14th to the 16th Century

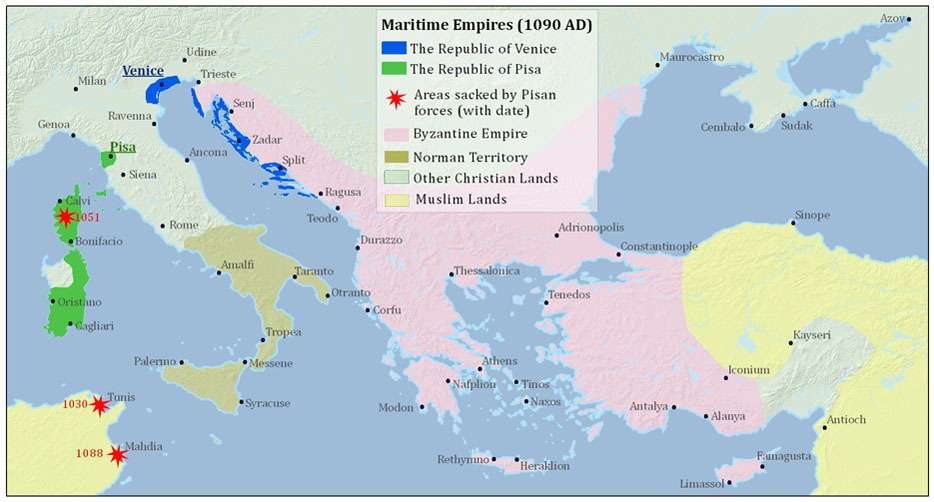

From the 11th century onward, Italian city-states such as Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice began to gain influence in Mediterranean trade thanks to the privileges granted by the Byzantine Empire. The first signs of this influence appeared during the reign of Alexios Komnenos. Unable to cope with the Norman threat, Komnenos sought assistance from Venice and, in return, granted them extensive commercial privileges. From that time onward, the Venetians were able to engage in free trade throughout the empire—even in Constantinople—without paying any taxes.[1] In subsequent periods, other Italian states also benefited from these privileges, settling in certain port cities along the Anatolian coasts and, in some places, succeeding in establishing autonomous colonies.[2]

At the beginning of the 13th century, one of the most striking events of the age took place: the conquest of Constantinople by the Latins. During this century, the rivalry between Venice and Genoa in the Mediterranean intensified. Both states were striving to obtain privileges from the Byzantine Empire. The Fourth Crusade became an opportunity for them in this regard. As is well known, the outcome of the Fourth Crusade resulted in the city remaining under Latin rule until 1261. In this period, the Byzantine Empire continued to exist centered in Nicaea. Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos aimed to recapture Constantinople but needed support to do so. At that time, Venice, the greatest power in the Eastern Mediterranean, was hostile toward Genoa. Aware of this, Michael forged an alliance with Genoa and seized Constantinople in 1261. In return for this support, the Genoese were granted commercial privileges and tax exemptions.[3] Thus, the Genoese now also gained the right to sail into the Black Sea. They soon proceeded directly into the Black Sea and founded a number of colonies. There, in accordance with agreements made with local rulers, the Genoese initially obtained small and weakly fortified territories in coastal regions, which they later transformed into strong fortresses.[4] Meanwhile, the Pisans had also acquired the right to trade in the Black Sea. However, the restoration of the Byzantine Empire increased Genoese influence while reducing the impact of Pisa and Venice. In 1282, Pisa supported Sinucello, who had risen in rebellion against Genoa and attempted to seize control of Corsica. In response, the Genoese undermined Pisan trade near the Arno River. War became inevitable, and a naval battle took place in 1284 between Genoa and Pisa. The Genoese fleet of 93 ships, commanded by Oberto Doria and Benedetto Zaccaria, defeated the Pisan fleet of 72 ships, led by Albertino Morosini and Ugolino della Gherardesca, in the Battle of Meloria. Venice, on the other hand, by supporting the Crusader coalition in 1282, caused security problems for its own people residing in Constantinople. For the sake of the safety of its subjects in the city and to maintain a presence in the Northern Aegean and Black Sea, Venice was compelled to reach an agreement with Byzantium. Consequently, peace was achieved between Venice and Byzantium in 1285.[5]

The year 1294 is of particular importance for the Genoese–Venetian struggle. When the city of Acre, the port through which the wealth of the Syria–Palestine region was conveyed, fell to the Mamluks, it was a devastating blow for Venice. As a result, Venice, in search of new opportunities, turned its gaze toward the Black Sea, an area under Genoese dominance. Thus, the Genoese–Venetian struggle, which had already extended across the Adriatic and the Eastern Mediterranean, now began to unfold in the Black Sea as well. The two states first confronted each other in the Gulf of Alexandretta, where the Genoese emerged victorious. They sank the Venetian trade fleet at Crete and Modon. In 1296, a Venetian fleet of seventy-five ships under the command of Ruggiero Morosini sailed toward the Byzantine coasts to take revenge on Genoa. That same year, earthquakes occurred in Constantinople and Western Anatolia. Spiritually shaken, the Byzantines received news, a week after the earthquake—on 22 July—of Venice’s attack on Galata. The Venetians also burned and destroyed the homes of the Byzantine population living in the area. Although the emperor wished to remain neutral, he was eventually compelled to enter the war in order to protect his people and prevent harm to innocent civilians, and he imprisoned the Venetians residing in the city. Having suffered losses in the conflict, the Venetian forces were forced to withdraw. After Byzantium entered the struggle, the conflict between Venice and Genoa ended on 25 May 1299. However, the Byzantine Empire remained at war with Venice. Mutual negotiations were held but did not yield the desired outcome. Moreover, Venice attempted to reach an agreement not through peaceful means, but by intimidating the Empire. On 21 July 1302, Venetian forces entered the waters of Constantinople and attacked the coastal areas and the Princes’ Islands. As a result, Venice was compelled to conclude an enforced treaty with Byzantium on 4 October 1302. With this treaty, the Venetians regained the commercial privileges they had previously enjoyed. The Genoese, however, did not lose their existing position. Subsequently, General Benedetto Zaccaria captured the island of Chios, initiating a long-lasting period of Genoese rule there.[6]

Later, in 1316, the Genoese secured a number of privileges by concluding a treaty with the Empire of Trebizond. Under this agreement, a consul was to be sent annually from Caffa, and a consulate building in Caffa was to be constructed at the emperor’s expense; the Genoese were also granted the right to own a church, a warehouse, a bakery, and a bath. More importantly, Emperor Alexios granted the Genoese the territories north of Daphnous, including the fortress of Leonkastron and the areas where their warehouses were located. The quay adjacent to this region would henceforth be used exclusively by the Genoese. From this date forward, Genoese ships docked at the pier in Daphnous, situated to the east of Leonkastron. Thus, the Genoese effectively acquired a commercial free zone in Trebizond. The Venetians, having lost their dominance in Acre, began seeking new commercial privileges. Within this framework, in 1319 they concluded a commercial treaty with the Empire of Trebizond. They obtained the right to conduct their trade throughout the empire by paying the same taxes and customs duties levied on the Genoese. Furthermore, they acquired a plot of land on which they could build homes, commercial establishments, and churches of their own. However, the Venetians failed to establish a stable colony there.[7]

By the 14th century, the rivalry between Venice and Genoa had reached its peak. From time to time, the Byzantine Empire and the Ottoman state also became involved in this competition. Perhaps the most intense phase of the Venice–Genoa rivalry occurred between 1350 and 1355. Venice declared war on Genoa on 6 August 1350. A series of battles followed. The Venetians were receiving very accurate information about the internal crisis in Byzantium. In August 1354, Maffeo Venier, the Venetian bailo in Constantinople, reported that Emperor John V Palaiologos was in alliance with the Genoese, while Emperor John VI was in alliance with the Turks. The subjects of Byzantium were in such distress and anxiety that they would have preferred to be ruled by Venice; yet they were also ready to place themselves under the protection of any foreign power—be it Serbian or Hungarian. The Venetians, however, were in no position to intervene, having become deeply embroiled in their war with Genoa. Since the naval battle in the Bosporus in 1352, the major clashes of this war had taken place in western waters, off Sardinia and in the Adriatic. The most critical phase occurred, however, in November 1354 at Zonchio, near Modon in the Peloponnese. Genoese admiral Paganino Doria sailed up the Adriatic almost as far as Venice, terrifying his enemies, then turned back and led his fleet into the Aegean Sea. Off Zonchio, he launched a surprise attack on the Venetian fleet of thirty-five galleys commanded by Niccolò Pisani. Thousands of Venetians were taken prisoner, and hundreds were killed. Pisani fled back to Venice. This was his final disgrace; he was dismissed from the navy and was never again entrusted with command. It was this disaster that finally drove Venice to the negotiating table in January 1355, resulting in the signing of a peace treaty with Genoa in June. The most revealing clause of the treaty was the mutual agreement that neither side would send merchant ships to Tana for three years. The conflict placed Genoa in such grave danger that it was forced to surrender its government to Gian (Jena) Visconti, Lord of Milan. For a time, therefore, Genoa came under the rule of the Duke of Milan. Later, however, a popular uprising drove the Visconti from power.[8]

In 1378, war between Venice and Genoa broke out again with full intensity. Genoa concluded an alliance with the Kingdom of Hungary. In August 1379, Genoa captured Chioggia, a small fishing port controlling one of the key exits to the Adriatic. In June 1380, the Venetian commander Vettor Pisani recaptured Chioggia and destroyed the Genoese fleet. Although this fierce maritime struggle brought Venice no formal advantages at sea, the Treaty of Turin signed in 1381 ended the war between the two republics and marked the beginning of Venice’s undisputed predominance.

As the Ottoman state expanded its territories in Western Anatolia and Europe, it also began to figure more prominently within the triangular relationship of Genoa–Venice–Byzantium. The Genoese had concluded a treaty with Orhan Gazi in 1352. Under this treaty, Orhan Gazi sided with the Genoese, providing supplies and military support to Galata. This policy of friendship with Genoa continued under Murad I due to plans directed against Byzantium. Above all, this policy enabled the Ottomans to charter Genoese ships in order to cross from the Dardanelles to Gallipoli. Indeed, beginning in 1363 and continuing until the time of Mehmed II, both the Genoese of Galata and those of Phocaea transported Ottoman soldiers and settlers from Anatolia to Rumelia in exchange for large sums of gold. Later, however, Murad I reacted negatively to a new treaty concluded in 1382 between Lorenzo Gentile, the Podestà of Pera, and Byzantine Emperor John V. In response, a new treaty was signed on 8 June 1387, renewing the earlier agreement concluded with Orhan Gazi. This renewed ahdname provided for free trade between the two states by specifying the taxes to be paid and the treatment of prisoners.[9]

By the end of the 14th century, Venice had emerged as the predominant power in the Mediterranean. In 1384, it occupied the island of Corfu in the Adriatic, gaining control over the entry and exit of the Adriatic Sea. Between 1407 and 1427, Venice also captured cities in the Terraferma such as Padua, Verona, Brescia, and Bergamo. Meanwhile, in 1405, Genoa had extended its rule over two coastal strips, one to the east and one to the west. As a result, Venice succeeded in establishing an empire of strategic and commercial significance across the Eastern Mediterranean, while Genoa maintained a relatively strong position in the Black Sea.

However, the chain of events that dealt a serious blow to Genoese dominance in the Black Sea began with the conquest of Constantinople. As is known, during the siege of the city, Genoese troops came to the aid of Byzantium and participated in the defense. This created a sense of hostility toward Genoa within the Ottoman ranks. Following the conquest, Genoese trade suffered greatly when control of the straits passed into Ottoman hands.[10] Genoa’s access to its Black Sea colonies was now effectively at the mercy of the sultan. The alternative route of the Danube River could not substitute for the strategic advantages of the straits.[11] The same held true for Venice. Access to Tana, Venice’s most important trading city in the Black Sea, was only possible via the straits.[12]

Although Genoese colonies such as those in Lemnos, Amasra, and Caffa (Theodosia) survived for a few more years, these settlements were eventually seized by Mehmed the Conqueror. The island of Chios continued to maintain its independence under the control of the Giustiniani family until 1566, when it was annexed to the Ottoman Empire following its conquest by Piyale Pasha.[13]

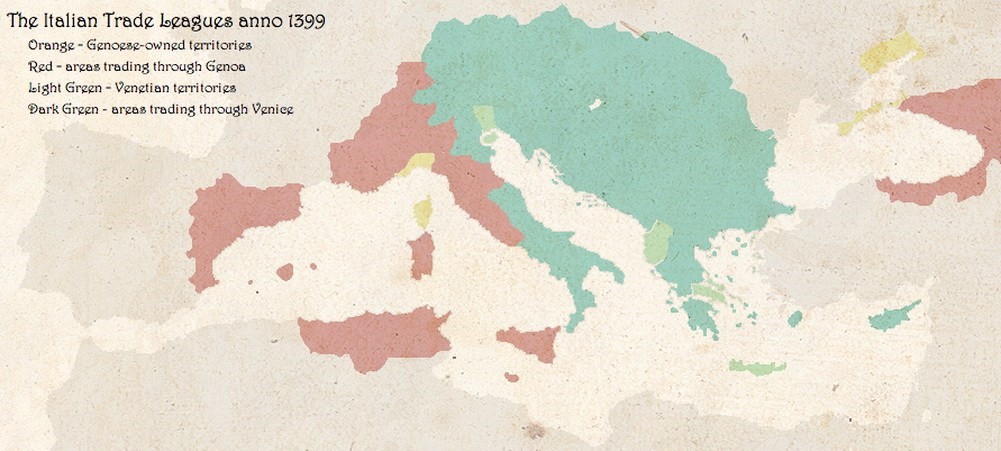

The Italian Trade League – 1399

Yellow: Genoese territories

Red: Genoese zone of commercial influence

Light green: Venetian territories

Dark green: Venetian zone of commercial influence

Despite political developments, Genoese and Venetian merchants continued to trade within Ottoman lands. From the early periods of the Ottoman state onward, Genoese merchants could be found in almost every city of the empire. The Ottoman sultans granted them the privilege of engaging freely in trade in ports, waters, and other locations within their domains.[14] However, in the 15th and 16th centuries, Genoese spheres of influence shrank significantly, and they increasingly fell under the domination of states such as France and Spain.

The Venetians, on the other hand, frequently entered into wars with the Ottomans during the 15th century in order to defend their territories against Ottoman expansion. The first of these wars occurred between 1415 and 1419 and resulted in the destruction of the Ottoman fleet. Subsequent wars took place in 1463–1479, 1499–1502, and 1537–1540.[15]

Bibliography

OSTROGORSKY, Georg, History of the Byzantine State, trans. Fikret Işıltan, Ankara, 2006.

GREGORY, Timothy E., A History of Byzantium, trans. Esra Ermert, Istanbul, 2021.

ÇAVUŞDERE, Serdar, “Selçuklular Döneminde Akdeniz Ticareti, Türkler ve İtalyanlar” [Mediterranean Trade, Turks and Italians during the Seljuk Period], Tarih Okulu, No. 4, 2009.

TEZCAN, Mehmet, “Türk-Moğol Hâkimiyeti Döneminde Karadeniz’de Ticaret” [Trade in the Black Sea during the Turco-Mongol Rule], Tarih İncelemeleri Dergisi, Vol. XXIV, No. 1, 151–194.

TANRIVERDİ, Ünal, “1261 Sonrası Bizans-Ceneviz İlişkileri ve Cenevizlilerin Galata’ya Yerleşme Süreci” [Post-1261 Byzantine–Genoese Relations and the Process of Genoese Settlement in Galata], Ortaçağ Araştırmaları Dergisi, Vol. II, No. 2, 214–226.

MILLER, William, “The Genoese in Chios 1346–1566”, The English Historical Review, Vol. XXX, No. 119, 418–432.

SEVER, İlker, “XIV. Yüzyılın Ortalarında Trabzon Komnenos Devleti – Ceneviz İlişkileri ve Ceneviz’in Giresun Baskını (1348)” [Relations between the Empire of Trebizond and Genoa in the Mid-14th Century and the Genoese Raid on Giresun (1348)], Uluslararası Giresun ve Doğu Karadeniz Sosyal Bilimler Sempozyumu, ed. Gazanfer İltar, Ankara, 2009, 108–116.

MADDEN, Thomas F., Venice: A New History, New York, 2012; Donald M. Nicol, Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations, trans. Gül Çağalı Güven, Istanbul, 2000.

GALLOTTA, Aldo, “Genoa”, TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, Vol. VII, 363–365.

FLEET, Kate, “The Treaty of 1387 Between Murad and the Genoese”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. LVI, No. 1, 13–33.

RUNCIMAN, Steven, The Fall of Constantinople 1453, trans. Derin Türkömer, Istanbul, 2018.

KIRK, Thomas Allison, Genoa and the Sea: Policy and Power in an Early Modern Maritime Republic, Maryland, 2013.

KHVALKOV, Evgeny, The Colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea Region, New York, 2018.

MILLER, William, “The Genoese in Chios 1346–1566”, The English Historical Review, Vol. XXX, No. 119, 427–429.

PARLAZ, Selim, “XV. Yüzyıl Balkan Topraklarında Osmanlı ve Ceneviz Ticaretinde Ceneviz Tüccarları ve Ticari Mallar” [Genoese Merchants and Commercial Goods in Ottoman–Genoese Trade in the Balkans in the 15th Century], in Balkan Tarihi, Vol. II, ed. Zafer Gölen, Abidin Temizer, Ankara, 2016, 285–296.

PEDANI, Maria Pia, “Venice”, TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi, Vol. XLIII, Ankara, 2016, 44–47.