The Author in Hell, All Its Terrible Aspects: Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Before Lev Nikolayevich turned to what was right and ethical, and before he began to teach wisdom through his voluminous books, his life was a hotbed of horrors. Tolstoy came from a noble family, and the way of life in his youth was completely opposed to the appropriate customs of the time. You might say, “What if we could shed light on his little-known dark life, what if we didn’t?” Of course, the author’s private life does not detract from the value of his works. But in this article, we wanted to deal with the magazine side of the business.

Kinship with Pushkin and Genghis Khan

Let’s say that initially Tolstoy had a kinship with Pushkin, at the same time there are theories that his lineage is based on Genghis Khan. Even if his connection with Pushkin is established, it would be quite unfounded to try to seriously explain that he was a descendant of Genghis Khan. As a result, some studies also claim that approximately 16 million people today are descendants of Genghis Khan. At this point, the possibility that Tolstoy’s lineage is also connected to Genghis Khan is not striking.

In his childhood and youth, he was lazy and played cards a lot.

Although Tolstoy was seen as a model for self-improvement, early in his life he was not very interested in matters of knowledge. His teachers used to say about him things like, “He can’t work and he doesn’t want to work.” Most likely, the young Tolstoy did not have time to study, indeed, he was quite busy gambling.

Many modern scientists directly call Tolstoy a good gambler. Even this addiction of his has opened many lessons per se. He once lost his mansion in Yasnaya Polyana during a gamble with his neighbor Gorohov. Worst of all, this was the house in which Tolstoy’s childhood and youth passed. After this bad incident, he constantly tried to get his old house back, but he could not succeed.

He lived a life full of evils and sins.

In “Confessions,” published in 1884, Tolstoy recalled his own teenage years in a chilling way and did not hesitate to speak of countless sins: he had been deceived, deceived and deceived. “Lies, theft, prostitution of all kinds, drunkenness, violence, murder… There is no crime left that I did not commit,” he wrote. In this respect, he was a writer who was exposed to many evils in his youth. Perhaps this is why he understood the aesthetic pleasure of evil, and in his later years began to preach the necessity of good.

His interest in women and his libido were disturbingly high.

Tolstoy had intense sexual desire for women. He found peasant women, in particular, irresistible. Her diaries were full of conquests about peasant women working on her property. In his diary of April 21, 1858, he wrote:

” April 21, 1858, is a wonderful day. Peasant women in the garden and fountain. It’s like I’m crazy.”

Tolstoy was not a handsome man, but he had a great sex drive. In addition to the thirteen children his wife Sonya had born, he had a dozen children of his own in the villages on his estate. While married to Sonya, he fell in love with a twenty-two-year-old woman named Aksinya Bazkina. She wrote in her diary: “I am more in love than I have ever been before in my life. Today he is in the woods. I’m an idiot. Monster. The bronze glow of his face and his eyes… I can’t think of anything else.” Tolstoy did indeed fall in love with Axina, but he never met her. A quarter of a century after the first encounter, he wrote that when he saw the “bare legs” of a peasant girl, he felt happy to “think that Axinia is still alive.” In other words, he continued to love her even when she was older. Tolstoy was not alone in this. As for his falling in love with the serfs working on his estate, Turgenev gave him a fateful companion. He, too, was famous for having a love affair with the peasants on his estates. He even had an illegitimate child.

He was terrified of death.

Judging from his diaries, we see that Tolstoy was a writer obsessed with death. This manifested itself not only in his books, in which he described with a kind of sadomasochistic delight the bodies of the dead and wounded dismembered in battle. Sometimes he himself was so afraid of dying that he would break out in a cold sweat and prepare for the time when his perseverance came. Especially these fears began to manifest themselves more acutely after 1860, when his older brother Nikolai died of tuberculosis in his arms. Tolstoy was a little over 30 years old at the time, but he became so depressed about his own imaginary “old age” that even then he began to go to the Bashkir farm Karalik for treatment.

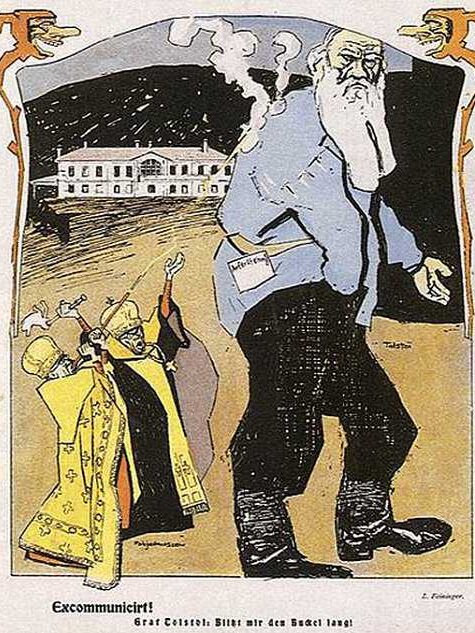

Excommunicated from church

Following the publication and popularity of Anna Karenina in the 1870s, Tolstoy, then in midlife crisis, became disgusted with his aristocratic origins and his ever-increasing wealth. After experiencing several emotional and spiritual crises, he questioned his faith, religion, and church organizations. He began to speak of the bribery prevalent among churchmen, the contradictions of interpretations of Jesus’ teachings with Christianity, empty religious rites, and the fall into “radical atheism.” He did not hesitate to scold and despise the state. That’s why he was put under tacit police surveillance. The Russian Orthodox Church could not accept these aspects of Tolstoy, and in February 1901 Tolstoy was excommunicated from the church.

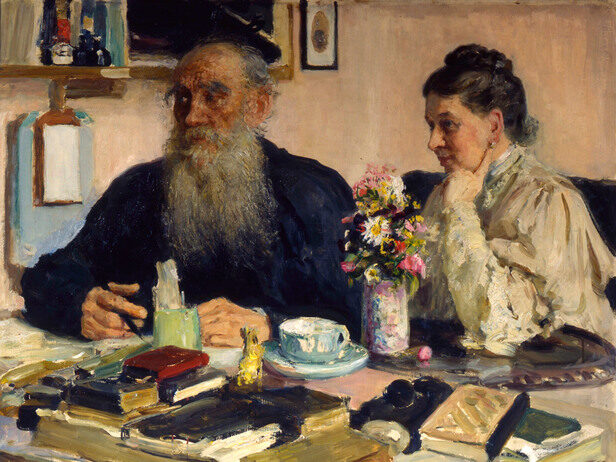

He belittled his wife from the night of their wedding until her death.

Despite the initial excitement of marriage and Sofia Andreyevna’s magnanimity (as a matter of fact, this woman wrote War and Peace exactly 7 times by hand), there was a terrible unrest in the marriage of the two. When they married, Sofiya was 18 and Tolstoy was 34. Before Tolstoy’s decision to marry, he had many mistresses and relationships with different women. He wrote about all the romantic experiences he wrote and described in his diaries, and it was thought that it would be honest for his wife to know all this. So right after her wedding, she gave them to Sofia and asked her to read them all. Sofia Andreyevna was horrified after all these pages and cried at length. As a result of this fact, he had a strong feeling that all his dreams were ruined. She gave her whole life, the first and the end, to Tolstoy, but she was just “another woman.” This situation was the cause of many conflicts that would occur in their future relationships.

The situation began to get worse and worse. Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, who was a very spiritual person, also stopped caring about family life; He began to wear peasant clothes and squandered his wealth, rejecting unnecessary wealth. Sofia and Tolstoy had 8 children, and Sofia struggled to save Tolstoy from bankruptcy and begged him to be more cautious. After these situations, Tolstoy decided that he had finally found the cause of his endless depression and ordeal, and wrote: “The name of my illness is Sonya.”

What kept Sofia alive was her children. The young woman was fighting for them and putting up with a monster like Tolstoy. But fortune had wounded him on this side as well; Unfortunately, although they had 13 children, seven of them had died, and these deaths had left deep wounds in Sofia’s soul.

In his later years, he seemed to go crazy and put all the blame on his wife.

The relationship of the spouses eventually deteriorated so much that they literally stopped putting up with each other. Tolstoy even asked for a divorce, but Sofia Andreyevna threatened to take Tolstoy his own life. Tolstoy could not accept to commit this sin. Now 82 years old, he decided he had endured enough and ran away from home in the middle of the night with the intention of settling in a small plot of land that belonged to his sister. Her doctor and her young daughter, Sasha, had left with him. They had traveled by train in a communal carriage.

The disappearance of the author caused a sensation in the media, and when he appeared at the Astapovo railway station a few days later, journalists, fans and his wife flocked there. Tolstoy, already very seriously ill at that time, refused to return home, and died of pneumonia on November 20, 1910, at the station director’s house. At that moment, his clock in the station building was stopped. Since then, the clock in the building of this station has always shown 6 hours and 5 minutes. The time of Tolstoy’s death…